Intro

Transforming the food system is a question of climate resilience and food security, and this is deeply complex and challenging. On the other hand, incremental change by singular asset investment, although positive, is too slow to bring about the change we need.

There is tremendous potential for a more systemic approach to investment programming, deployment and management in agriculture.

Next is an introduction to systems thinking … please note this is not an attempt to explain the field fully but rather to create common ground for understanding the complexities behind the food systems.

-----------

A brief intro to systems thinking

Systems thinking is a way to make sense of the world's complexity by looking at it in terms of wholes and relationships rather than by breaking it down and focusing on individual parts.

A system is a set of interconnected elements that produce their own rules or patterns of behaviour. In other words, each element presents its individual behaviour. And these elements together produce a set of behaviours that is different from that of its own.

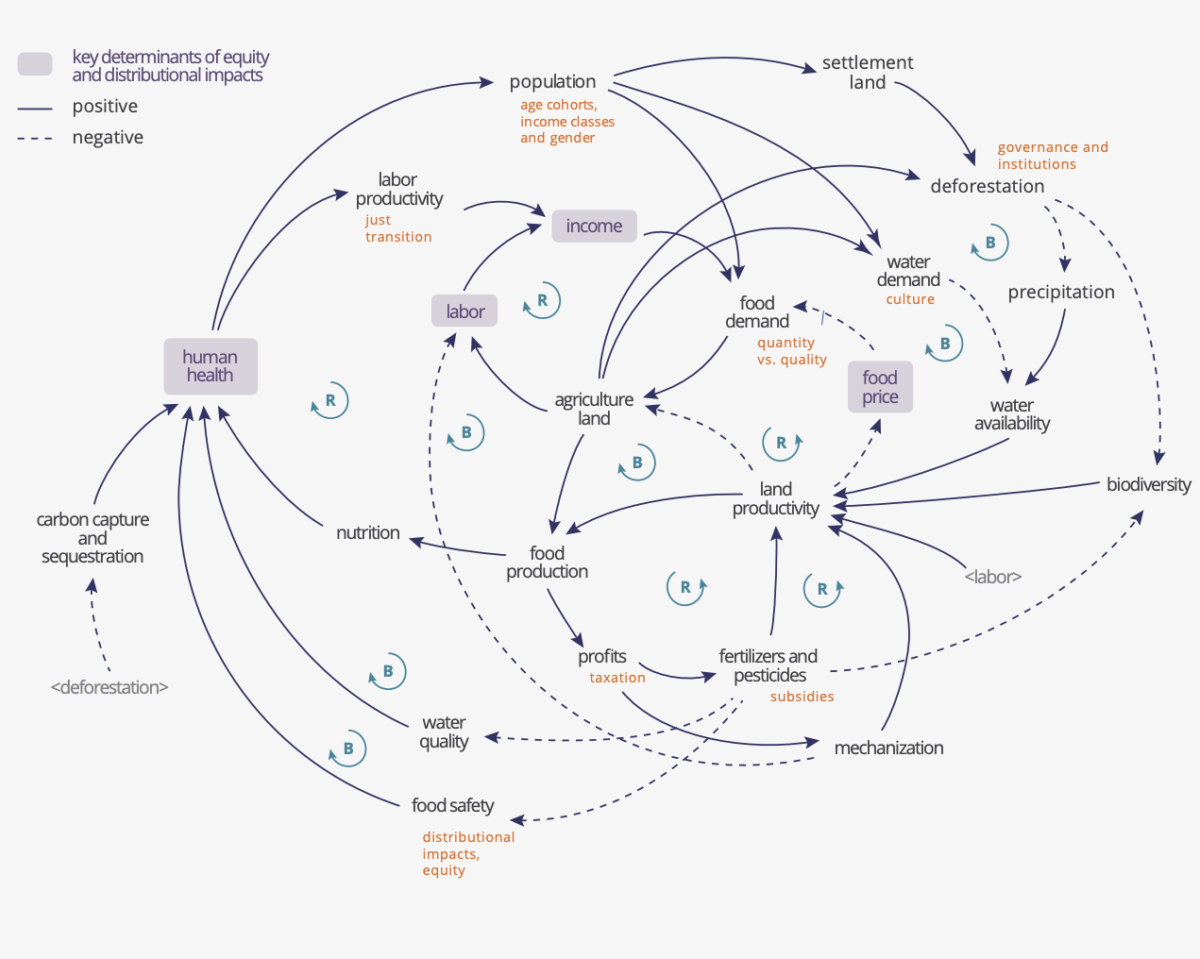

Because elements are interconnected, there are constant flows and feedback loops among elements of a system. By understanding flows and feedback loops, we can see how one part affects another (or many others) and ultimately affects the entire system. A critical consequence of intervening on individual elements is that you may miss critical synergistic opportunities or, worse, create unintended consequences.

Following is an illustrative example of different elements, flows and feedback loop interactions in a generic food system.

Systems take many forms, such as ecosystems, social structures, immune systems, transport systems, religions, organisations, etc. Systems thinking allows us to see the world as a web of connections and system mapping can help us identify leverage points, where a slight shift in one element can produce significant changes in others and the system at large.

One tenet of systems is that they are dynamic and constantly changing. Harnessing this dynamism towards reframed goals for a system can change how the whole system operates.

Insights into the food systems

“The world is a complex, interconnected, finite, ecological– social–psychological– economic system. We treat it as if it were not, as if it were divisible, separable, simple, and infinite. Our persistent, intractable global problems arise directly from this mismatch.” Donella Meadows, 1982: Whole Earth Models and Systems

The food system extends beyond production and consumption, encompassing a natural system shaped by intricate interactions of biological and climatic factors at local, regional, and global scales. For instance, global dynamics have caused elevated overnight temperatures in Indiana, affecting local corn and soy yields through increased plant respiration, reduced sugar availability for grain production, and altered pollination success.

These natural systems are intertwined with social, cultural, and economic systems that facilitate food production and distribution through market infrastructure, corporate strategies, government policies and consumer preferences. For example, the recent surge in organic produce markets can be attributed to factors like implementing organic certification and regulation, changing consumer preferences, price premiums and corporate strategies.

Technology, information and culture are also pivotal in how we produce, distribute and consume food, influencing interactions among these systems. Ultimately, our health and the planet hinge on the multitude of interconnected systems and the choices we, as consumers, make within them.

(Source: TEEBAgriFood and Nourish initiative n.d)

It is imperative to remember that the notion of a universal global food system is a misconception. It is true that international commodity markets exist, and many products are cultivated in one region before being distributed worldwide. However, the factors influencing demand and those affecting supply, frequently emphasize the significance of local context over global dynamics. The transformation of food systems necessitates a fundamental shift in our dietary preferences, market dynamics and how food is produced. This is attributed, in part, to the fact that our food choices reflect our cultural identity. Furthermore, local economic conditions, climate, policy frameworks and traditions significantly influence farmers’ decisions on what crops to cultivate and where to sell them.

What’s next?

Food systems are the quintessential complex adaptive systems. Transforming them requires a broad-based approach. A systems diagnosis is needed to understand the complexity that lies in the nexus of ecology, agriculture and food. By diagnosing the interactions and trade-offs among the region's different sub-systems, we can identify possible leverage points that could move the system towards a more desired dynamic.

Over the next year, we intend to produce a systems diagnosis of the food systems by looking at the links between elements, drawing out causal loops and identifying investable intervention points with the potential to create positive systems dynamics.

Transforming the food system requires a new and broad-based approach to systems change. We will probably need all the tools in our systemic investing toolbox: equity and debt capital, infrastructure finance, technical assistance grants, tax incentives and subsidies, supply chain finance and advanced market commitments, and new insurance products, to name just a few.

Get involved

To learn more about our motivation and the starting point of our activities around the Regenerative Agriculture prototype, check out our prototype home page.

If you would like to be involved, get in touch via community@transformation.capital and continue reading about the ideas fuelling the TransCap Initiative here.