The farmers trap is a vicious loop driven by interconnected economic pressures and unsustainable agricultural practices. At the heart of this cycle lies short-term contracts and loans, which dominate the U.S. farm operation and financing landscape–with approximately 40% of U.S. cropland leased and figures reaching as high as 60% in states like Illinois. Short-term leases favor short-term funding, and they are incompatible with the time needed to transition land to regenerative practices (read more about this here). These fleeting arrangements force farmers to prioritize short-term yield maximization over long-term regenerative practices, driving them towards intensive farming methods that degrade soil health.

Short-term yield maximization harvesting techniques deteriorate soil health and increase dependency on synthetic fertilizers and pesticides to maintain production levels, further compounding the damage to the land and escalating input costs. These dynamics create a vicious loop of continued short-term optimization at the expense of long-term soil resilience.

These rising input costs, alongside ever-increasing land prices, squeeze farm profitability, making it increasingly difficult for farmers to sustain their operations or consider expansion. This economic strain leads to a concentration of land ownership, where fewer entities control larger swathes of land, further raising barriers for new or existing farmers who wish to expand or transition to more sustainable practices.

“In 1990, small and medium-sized farms accounted for nearly half of all agricultural production in the U.S. Now it is less than a quarter.”

This land concentration and corporate monopoly have extinguished many small businesses at the expense of farming communities. This has exacerbated the rural-to-urban exodus as individuals, particularly the younger generation, leave, searching for better opportunities in urban centers.

This migration reduces the pool of potential next-generation farmers, creating a demographic vacuum in rural areas. The remaining farmers, often bound by the same short-term constraints and steeped in conventional practices, continue to employ intensive agricultural practices that promise immediate returns but jeopardize long-term resilience.

Breaking this cycle necessitates systemic changes that go beyond individual farming practices. This includes implementing supportive financial policies, community-based initiatives, incentives towards small businesses, and innovative financing and assistance that supports decentralized farmland ownership.

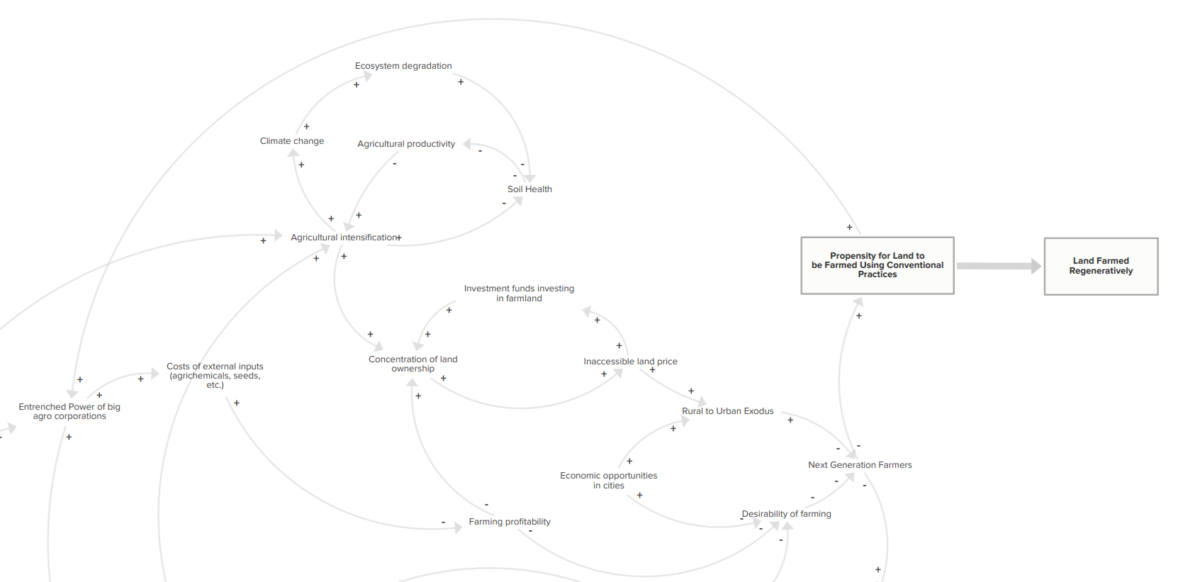

Below is a visual representation of these nodes and connections that describe the farmers’ trap. This illustration is part of our regenerative agriculture transition map, which we will be releasing soon.

Breaking the cycle: improving access to land

We will now zoom into one leverage point to address the farmer’s trap: increasing access to land ownership and facilitating sustainable long-term leases. Access to land is a pivotal factor in the transition to regenerative agriculture, as owners are more likely to invest in the land and adopt sustainable practices when they can reap the full benefits of their investments.

One key intervention strategy is to support equitable access to land for new, young, and historically disadvantaged farmers. This addresses entrenched power imbalances and promotes diversity and inclusivity that can enhance community and ecosystem sustainability. With only 2% of rural land in the US owned by people of color, innovative financing strategies such as community land trusts, cooperative ownership models, and targeted financing are critical for facilitating equitable land ownership.

Additionally, offering technical assistance for land acquisition is crucial. This support helps farmers navigate complex processes, access financial resources, and build confidence and networks. Such targeted support is especially beneficial for historically disadvantaged groups, enabling them to overcome systemic barriers and increase land ownership.

Financial support and innovative loan programs will also be vital. One possible tool is lease-to-own programs that can lower the barrier to land ownership by allowing farmers to lease land with a structured path to ownership. This model will enable farmers to gradually build equity in their farmland, making it more affordable and accessible.

Other examples are loan terms that valorize regenerative agriculture, which might include reduced interest rates, extended repayment periods and lower down payments to make land ownership achievable for farmers committed to regenerative practices.

Strategic investment portfolio

Disrupting a systemic challenge like the farmers’ trap will require a portfolio of interventions, as single-asset investments or even multiple assets within a similar area are highly unlikely to transform systems. Other nodes, such as farmer community networks, small businesses, and regenerative farming capacity-building programs, must also be catalyzed to introduce new dynamics capable of shifting systems. This is necessary to alter the system’s structure and, consequently, its rules and behavior.

In traditional finance—whether conventional or purpose-driven—the dominant portfolio composition paradigm is risk reduction through diversification. In systemic investing, the paradigm shifts to value maximization through synergy. In a strategic investment portfolio, the assets are selected according to a theory of transformation. In other words, for each asset, there is a narrative about how that asset is expected to contribute to change effects in line with the investor’s hypothesis of how systems change might happen, both on its own and through ‘combinatorial effects’ generated with other assets.

An example is investments in small businesses that create quality jobs and strengthen rural communities. These businesses could supply inputs for regenerative practices, local seeds and equipment, offer consulting and technical services, or process and market regenerative products. By creating a network of support around regenerative agriculture, these businesses help stabilize the local economy, making it less reliant on conventional agricultural practices and more resilient to market fluctuations and environmental changes.

Moreover, these small businesses often act as community hubs, providing education, resources, and support for regenerative practices. They foster a sense of community and collective action toward sustainable agriculture by organizing workshops, training sessions, and community events. This engagement empowers local farmers and residents, building a shared commitment to environmental stewardship and sustainable development. Aggregating these interventions can help retain young people in rural areas and attract new residents.

Conclusion

Realigning incentives within agricultural financing and land tenure systems can create a landscape where regenerative practices thrive, empowering farmers to drive the transition toward a more sustainable and just agricultural paradigm. Supporting historically marginalized farmers helps to restore power imbalances and improve land stewardship.

Combining these efforts with investments in small businesses that provide high-quality jobs in rural communities, alongside the development of rural networks and community hubs, can foster economic growth and well-being. These new dynamics could reduce rural-to-urban migration and equip next-generation farmers to lead the shift to regenerative agriculture. This transition promises enhanced soil health, reduced dependency on synthetic inputs, and offers a blueprint for revitalizing rural economies while strengthening the resilience of food systems.

Sources

- Horton, H. (2019). American food giants swallow the family farms in Iowa. The Guardian. Retrieved from

- Iowa Farm Bureau. (2021). Midwest ag land ownership vs. rental.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. (2024). Farmland value.