Definition

At an abstract level, systemic investing is an investment logic that enhances those sustainable finance practices that aim to bring positive change into the world. By “logic” we mean a coherent combination of intent, mindset, and method which — when operationalized — leads to an investment approach that is markedly different from sustainable and (traditional) impact investing.

That said, today there is no widely agreed-upon definition of systemic investing. In fact, our own definition is still evolving. What we tend to use most often at the moment is this:

Systemic Investing → The strategic deployment of diverse forms of capital, guided by a systemic theory of change and nested within a comprehensive systems intervention approach, for the purpose of funding the transformation of human and natural systems.

There are other initiatives working at the nexus of finance and (socio-technical) systems change, using different names such as systems-level investing, systems-based investing, and transformative investment. All of these tend to represent variations not only in nomenclature but also in approach. As part of the TransCap Initiative’s research agenda, we will seek to work with others to create a taxonomy that defines these approaches and allows us to categorize different flavors of all things systems+money.

Relevance

Conceptually, systemic investing is a response to the failure of traditional (impact) investing to generate transformative effects in the socio-technical systems on which humanity depends: cities, food and agriculture, mobility, coastal zones, industrial supply chains, forests, and the like. A holistic critique of these approaches, as well as the comprehensive argument for a new systemic investing logic, is presented in the TransCap white paper.

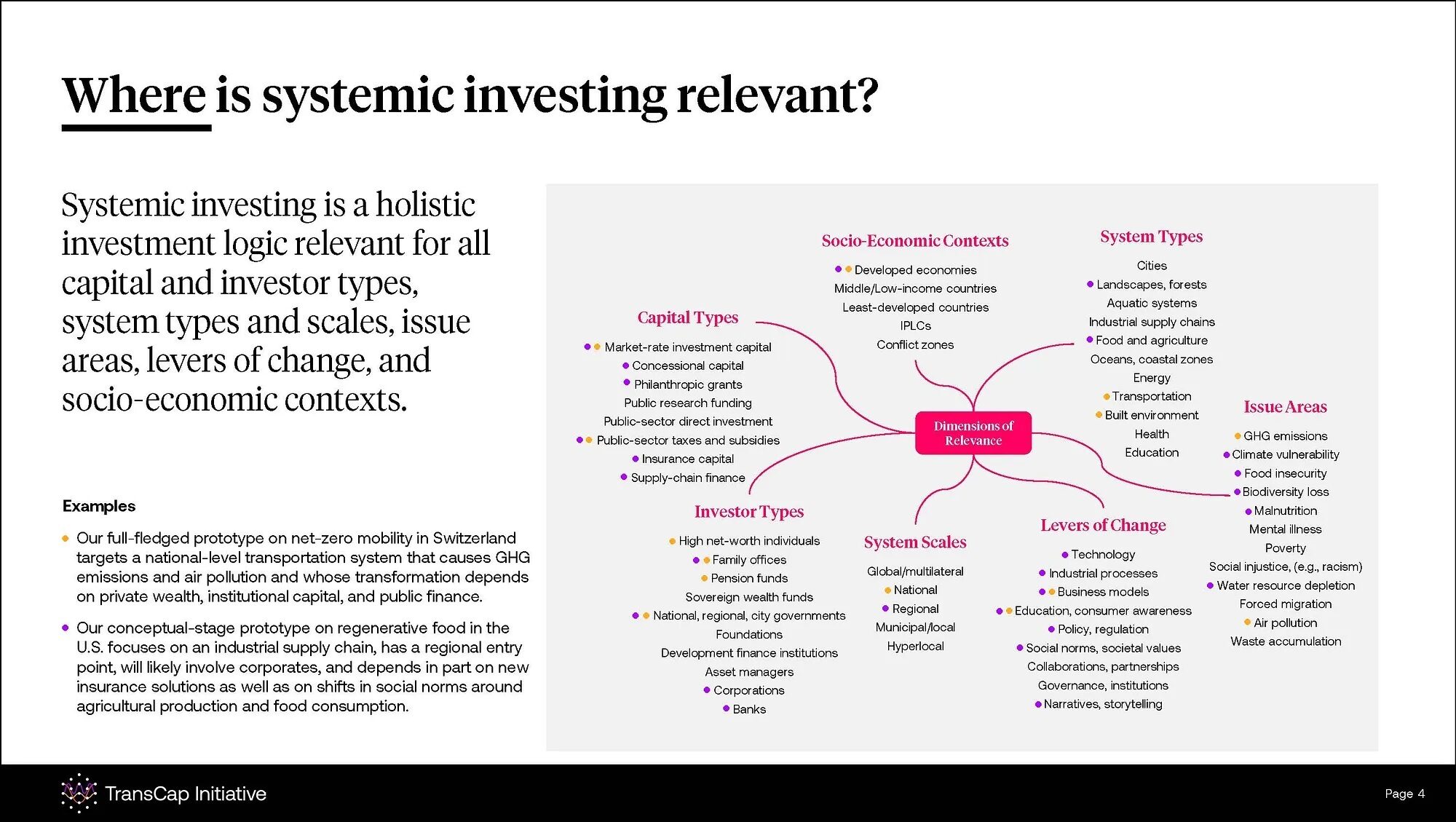

Practically, we believe systemic investing’s core ideas are relevant for almost all system types, system scales, socio-economic contexts, issue areas, levers of change, capital types, and investor types. And while there’s nothing inherent in the theory of systemic investing that dictates that systems must be defined along geographic dimensions, systemic investing is particularly relevant for place-based systems change work.

Socially, we believe systemic investing is relevant for a wide range of stakeholders in the finance world, including governments and development finance institutions, foundations and philanthropists, private-wealth and institutional impact investors, as well as large corporations and family-owned businesses. That’s because changing systems often means that a multitude of different kinds of capital — provided by different capital holders and financial intermediaries — need to be coordinated strategically in order to fund vast swaths of interventions that, in combination, have the potential to trigger transformative effects.

Yet what’s important to keep in mind is each of these actor groups looks at the challenge of funding systems change through their own unique lenses. This means that we need to adapt the narratives and words we use when explaining the relevance of systemic investing to different audiences. For instance, foundations tend not to see themselves as investors but rather as funders, which is why we tend to use the term “funding systems change” in lieu of “systemic investing” (cf. our recent article on the relevance of our work for philanthropy).

Hallmarks

While there may not be a solid definition of systemic investing yet, there are certain hallmarks that allow us to spot it and differentiate it from other sustainable finance approaches. At the highest level, these hallmarks include:

- Setting a transformative intent for the evolution of a natural or human system of interest

- Adopting a systems mindset in framing challenges and conceiving intervention strategies within that system of interest

- Using analytical tools from systems thinking and complex systems science, as well as methods from systems innovation and social change work, in grasping and quantifying the problem space and developing theories of change and intervention strategies

- Conceptualizing and measuring progress by studying the health of a system and/or systems-level properties (structure, feedback loops, etc) rather than end-of-causal-chain outcome metrics (e.g., CO2 saved)

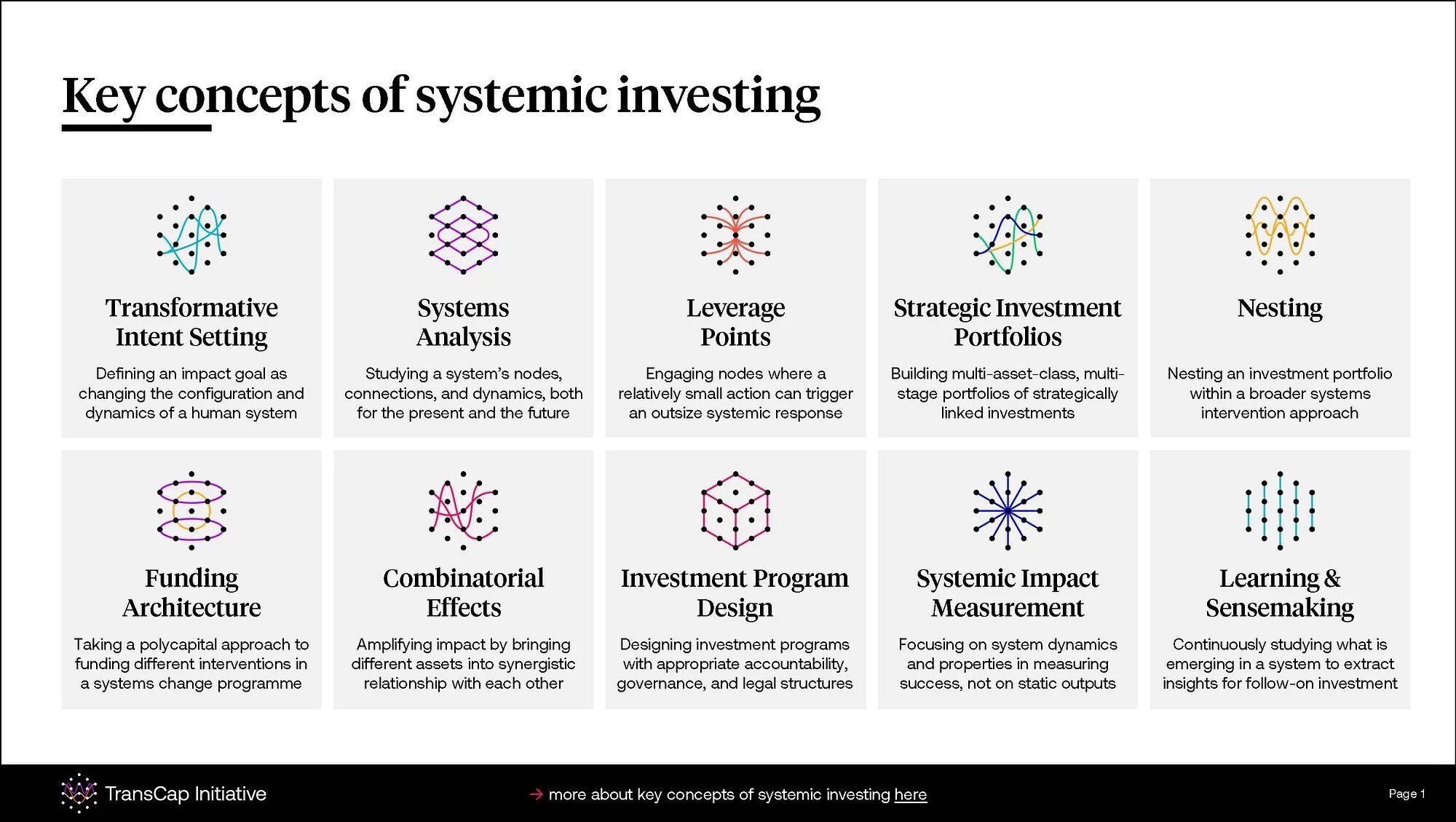

Practically, there is a set of key concepts that we have started to work with, including systems mapping, leverage points, investment portfolios, and funding architecture. You can read more about these here.

Difference

The DNA of systemic investing is still investing: the deployment of capital with the expectation of recouping the principal and generating some form of return. That said, systemic investing makes us revisit how capital is deployed, what kinds of capital we need to deploy in order to trigger systemic effects, and what constitutes reasonable expectations regarding impact and financial risk and return.

For instance, we tend to work with an expansive definition of “capital”, one that includes a broad range of financial forms of capital: market-rate investment capital, concessional capital, public finance (subsidies, taxes, public procurement, etc.), corporate finance (direct investments, supply chain finance, advanced market commitments, etc.), insurance products, and philanthropic grants. We also include social, human, and political capital in our toolbox. That’s because all these different kinds of capital have their role to play in a funding architecture that underpins systems change work.

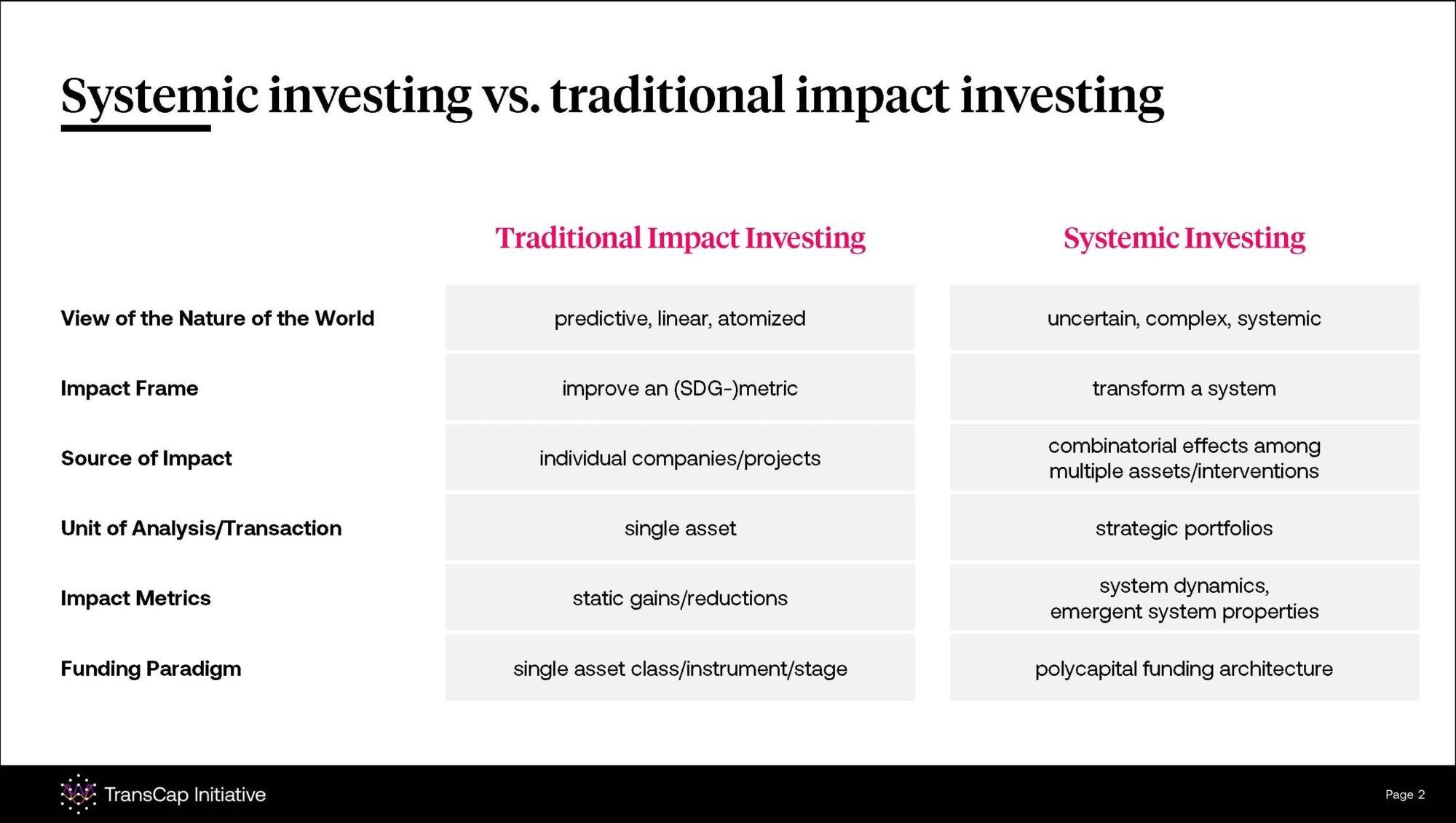

We are often asked how systemic investing is different from traditional impact investing. The most striking divergence is to be found in the fundamental question of how transformational change happens in the world. Most traditional (impact) investing assumes that transformative change can emerge from single technologies, projects, or social enterprises. We call this the “single-asset change paradigm”. In contrast, systemic investing assumes that systems change is most likely the effect of multiple shifts happening within a system at the same time and with a degree of strategic coherence, which means that the challenge is to develop a funding architecture capable of directing different forms of capital to enable a multitude of intervention under a transformative theory of change.

Examples

In our own work, we are experimenting with applying the core ideas of systemic investing in different contexts.

For instance, in our most advanced prototype, we are running a systemic investment program aimed at transforming the Swiss mobility system. This work first focused on defining the system boundaries and clarifying our change intent. We then conducted a multi-stakeholder process to map the system (both in the present and future), identify leverage points, and develop a transformative theory of change (more here). This then enabled us to develop an intervention strategy, the basis for building a pipeline of financeable interventions and structuring funding vehicles (ongoing).

Yet we are by no means the only — let alone the first — organization exploring systemic investing. For instance, in 2014, the venture philanthropist Jesse Fink launched an initiative that would lead to the creation of ReFED, a non-profit dedicated to building a sustainable food system by bringing new philanthropic and investment capital — along with technology, business, and policy innovation — to the food waste challenge in the United States (cf. detailed case study developed by researchers at the MIT Sloan Sustainability Initiative). And there are other examples, including Builder’s Vision’s work on oceans, Kresge Foundation’s “Woodward Corridor Investment Fund”, and McKnight Foundation’s GroundBreak Coalition.

Building the field

Systemic investing is a nascent financial practice. To advance it, we need to further develop its conceptual underpinnings, put the theory into practice through real-world prototyping, and build the field through education, convening, and storytelling. This, then, is the mission of the TransCap Initiative. To learn more about what we do, check out our strategic plan, and reach out if you’d like to get involved.